Art Works |

Video |

||

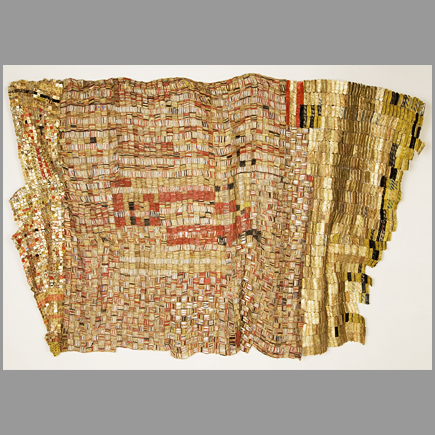

Meeting of the Elders, 2005

Meeting of the Elders, 2005 Aluminum bottle caps from African liquor bottles, copper wire; 79 x 135 inches From Beyond the Erotic: Flows |

Return to: Artist Biographies

|

||

El Anatsui's preferred media are clay and wood, which he uses to create objects based on traditional Ghanaian beliefs and other subjects. He has cut wood with chainsaws and blackened it with acetylene torches; more recently, he has turned to installation art. Some of his works resemble woven cloths such as kente cloth. Anatsui also incorporates uli and nsibidi into his works alongside Ghanaian motifs. El Anatsui has exhibited his work around the world, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2008-09); National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. (2008); Venice Biennale (2007); Hayward Gallery (2005); Liverpool Biennial (2002); the National Museum of African Art (2001); the Centro de Cultura Contemporania Barcelona (2001); the 8th Osaka Sculpture Triennale (1995); and the Venice Biennale (1990). A retrospective of his work, subtitled When I Last Wrote to You About Africa opened at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, in October 2010. It will be touring North America for the next 3 years. What does Uli mean? The drawing of uli was once practiced throughout most of Igboland, although by 1970 it had lost much of its popularity, and was being kept alive by a handful of contemporary artists. It was usually practiced by women, who would decorate each other's bodies with dark dyes to prepare for village events, such as marriage, title taking, and funerals; designs would sometimes be produced for the most important market days as well. Designs would last about a week. Most uli designs were named, and many differed among various Igbo regions. Some were abstract, using patterns such as zigzags and concentric circles, while others stood for household objects like stools and pots. Some represented animals such as pythons and lizards; others showed plants, like yam leaves, or heavenly bodies, including a crescent moon and stars. Still other designs depicted cutting and other actions. The use of uli was not limited to the human body. Igbo women would also paint murals of designs on the walls of compounds and houses. These generally used four colors which could be created from natural bases easily found in the area; black was made from charcoal, reddish brown from the camwood tree, yellow from either soil or tree bark, and white from clay. When the British arrived in the area at the turn of the twentieth century, they brought with them a commercial laundry additive which some painters used to create blue pigment. Uli was not only meant to express a specific message. It was also meant to beautify the female body and buildings to which it was applied, as beauty is equated with morality in Igbo culture. Today the practice of uli is being kept alive by, among others, the artists of the Nsukka group, who have appropriated its designs and incorporated them into other media. What does Nsibidi mean? There are thousands of Nsibidi characters with over 500 recorded. Nsibidi was once taught in school to children. Many of the signs dealt with love affairs; those that dealt with warfare and the sacred were kept secret. Nsibidi is used on wall designs, calabashes, metals (such as bronze), leaves, swords and it is used for tattoos. Nsibidi is primarily used by the Ekpe secret leopard society (also known as Ngbe or Egbo) and is used all over the Cross River region by Ekoi, Efik and Igbo people as well as other related peoples of who the Ekpe society is active amongst. Outside knowledge of Nsibidi came in 1904 when T.D. Maxwell noticed the symbols. Before the British colonisation of the area, Nsibidi was split into a sacred version, and a public, more decorative version which could be used by women. Aspects of colonisation such as Western education and Christian doctrine drastically reduced the number of Nsibidi-literate people leaving the secret society members as some of the last literate in the symbols. Nsibidi was and is still a means of transmitting Ekpe symbolism. Nsibidi was transported to Cuba and Haiti via the Atlantic slave trade, where the Anaforuana and Veve symbols stem from Nsibidi. |

|||